“We are free!”

Scipio and Fannie heard these words as teenagers in Mississippi. They likely repeated them over and over to themselves and others.

Individually, they heard the news of impending freedom sometime between September 22, 1862 (the announcement of the Emancipation Proclamation; effective on January 1, 1863) and the Confederate Army’s surrender in April 1865.

Scipio and Fannie were the parents of Will Barnes, my father’s grandpa. I have warm memories of visiting “Grandpa Will” and I’m grateful he lived until I was 12 years old. I sometimes wonder about their initial response to the news. Was it immediate celebration? Was it mixed with uncertainty and skepticism about the real impact of the proclamation? I can only imagine their swirl of emotions.

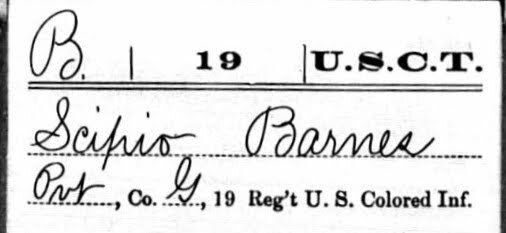

I can confirm that Scipio learned of freedom by 1864. He enlisted in the U.S. Colored Troops (USCT) on January 10, just days after this new division of the Union Army was formed on January 1, 1864.

Black folks knew that freedom would not be achieved without a fight. They were correct in believing that most enslavers would reject the mandates of the Emancipation Proclamation. That’s why, as soon as they were allowed to join the fight, Scipio and nearly 200,000 other Black men fought for freedom by serving in the USCT.

Fannie would have heard the news of freedom while toiling on the Mississippi plantation of her enslaver, Dr. Hussey – who was also her biological father*. I encourage you to let that sink in. Ponder the implications of his relationship with his “property”; resist imagining a love story between him and Fannie’s mother. (*Confirmed by my DNA match with one of Hussey’s descendants.)

Private Scipio Barnes mustered out of Company G, 19th Regiment, United States Colored Infantry on January 15, 1867. I don’t know when he and Fannie married, but the first of their eight children was born in 1873. It brings tears to my eyes whenever I see them, alongside Great-Grandpa Will and siblings, listed on the 1880 census. They were listed as farmers (i.e., sharecroppers) in Verona, Mississippi.

Slavery in the U.S. was not “officially” abolished until December 6, 1865. Sadly, this was followed by the too-brief Reconstruction Era, when attempts to guarantee rights through the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments were essentially nullified by state and local regulations (“black codes”, Jim Crow laws), and the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling of “separate but equal” in 1896.

Whenever progress is experienced, backlash follows.

By 1900, Scipio, Fannie, and their growing family were again legally marginalized. They were subjected to the wide-ranging impacts of the doctrine of White Supremacy, extending from everyday humiliations to racial terror.

Like so many others, they experienced only partial freedom. It would be over one hundred years later – even after my birth – before freedom’s accompanying legal rights would be secured for Black Americans.

Along the way, they lived, loved, and worked. Their descendants, my family, served in the military through five wars despite not being afforded equal rights. Still, they continued to hope and fight for freedom, many participating in the civil rights movement.

Although not formally recognized as a national holiday, starting in the 1980s, Juneteenth (aka Emancipation Day or Freedom Day) became a time for celebration and personal reflection for me on my family’s contributions to the struggle for freedom.

That struggle continues today when many of the aspects of the history I just shared are being challenged. Because these events contain what some now label “divisive concepts” that cause “discomfort, anguish, or guilt” they are being omitted, even erased from history courses. For that reason, we must learn one of the many lessons from Scipio and Fannie’s lives: freedom requires continuous effort.

On this Juneteenth, I invite you to join me in reflecting and seeking ways to actively engage in this struggle as peacemakers, not peacekeepers, who seek justice, love mercy, and walk humbly with God.

Nina Barnes is a trained spiritual director and coach with a passion for accompanying others in navigating life. Through Transforming Journey, her spiritual direction, and coaching practice, Nina creates space for people to discover purpose & meaning, discern opportunities, work through challenges and conflicts, and develop as leaders. Nina considers it a sacred privilege to help others experience and embody love, hope, redemption, and a journey of belovedness. She currently serves on the Board of Directors for Global Immersion, along with the Board of another non-profit in Minnesota.